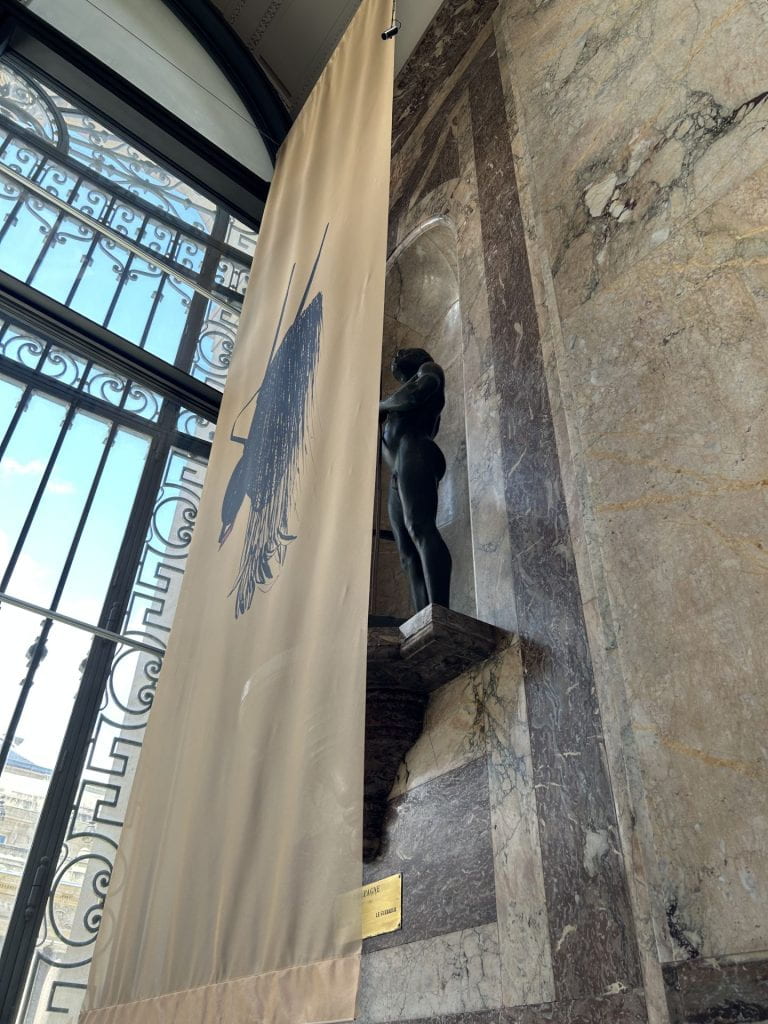

Being abroad these two weeks has been an eye opening experience. Not only was I able to learn more about colonial Africa and how the Europeans not only played one of the biggest roles, but I was also able to physically see the monuments and artifacts. Seeing artifacts only because they were stolen and looted, puts into perspective how imperialist societies gained their control. This experience has also helped me realize that though whole groups of people have been colonized and put through horrible conditions, it is not their only narrative.

Learning of controls such as “gatekeeper states” enacted by European empires that have caused African countries to be in a vicious cycle of dependence has been especially difficult. Gatekeeper states refer to countries that are run by an authoritarian government that only wants its people to work for the sake of their economy and export resources. Gatekeeper states are only geared toward extraction for the benefit of the metropole, making them resource-rich but socially poor. It is wearisome knowing that certain African countries, like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, will most likely not be economically, politically, or even socially free anytime soon solely because of the European nations. Teaching people, especially future generations, about the effects of colonial rule will spark the need for change from people everywhere.

It is very easy for the outside world to see oppressed people and feel that their only story is not being treated equally, when in reality that is not the case. Though indigenous groups of people from the Americas to the islands in the Pacific Ocean have been a victim of imperialism, either directly or indirectly, through it all they are resilient and refuse to comply with colonial rule.

While at the Tropenmuseum, there were spaces to celebrate culture from the exhibition “Things That Matter.” Each box housed a different question, starting with “When is culture yours?” to “How do you create new life?” These questions allow for people, of all backgrounds, to really reflect on their culture and what is truly theirs. It can be difficult when imperialistic societies take not only artifacts and people from their colonies, but peoples’ cultures and traditions. People may rely on the help of gods and ancestors to create new and sustaining life and give them something to hold on to during times of uncertainty. During the time spent learning about colonial rule in Africa, it can be hard to remember that everyday people (like you and me) were affected and their lives lost. Also located in the Tropenmuseum, laid an interactive tablet that allowed the viewer to see and commemorate the names of all enslaved people in Dutch history– this included those from the Caribbean and Asia. More than just their names, they also show their social relationship in their community.

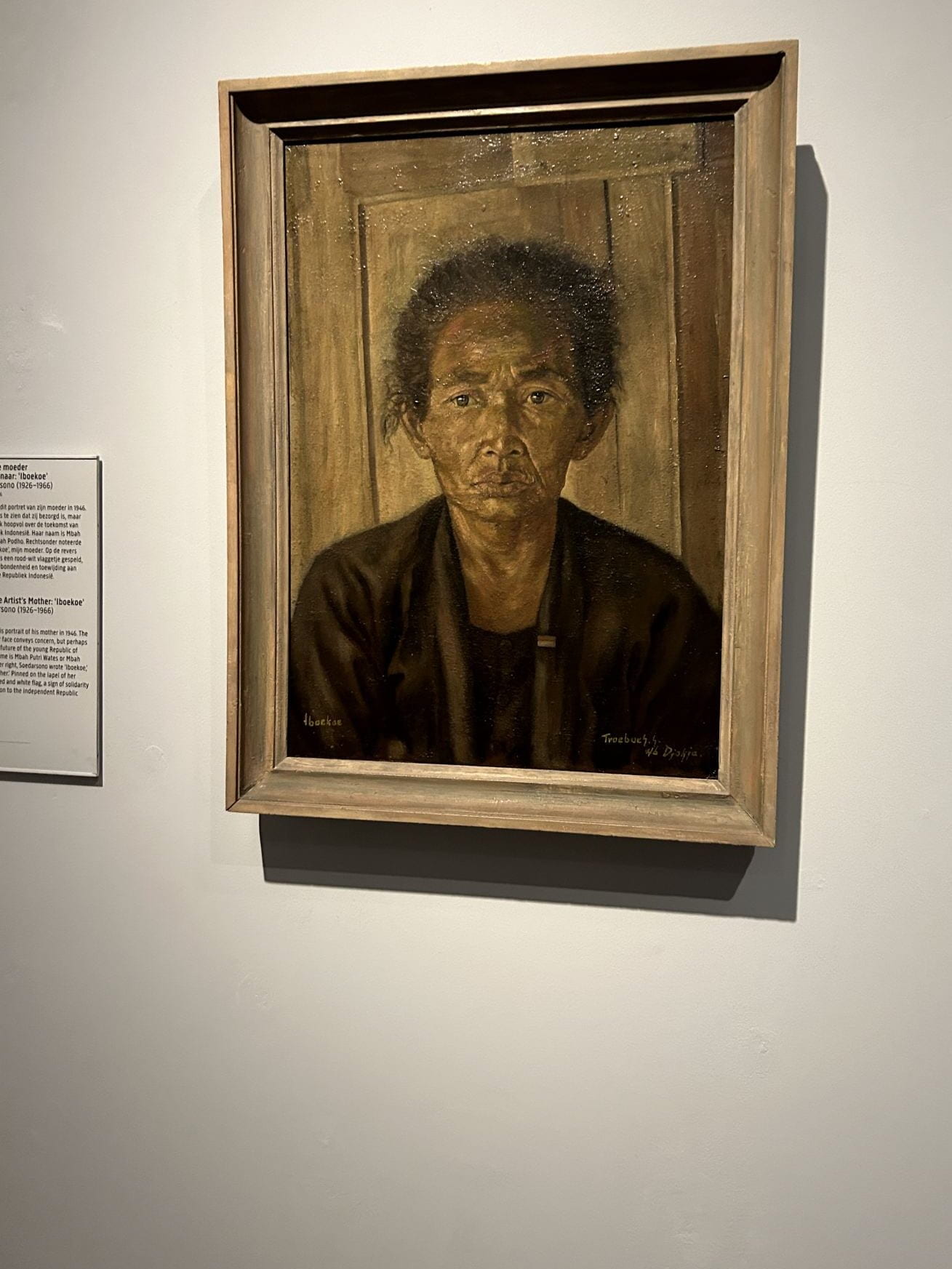

In the Rijksmuseum, there is an oil painting of an Indonesian artist, Trubus Soedarsono, mother. Though the painting captures her wearing a concerned look, she also glints hope for Indonesia. His mother also is seen wearing a pin of the red and white flag of Indonesia that holds the meaning of “solidarity… and dedication.” Colonists not only used violence to acquire land and labor, but they stripped people away of their culture and religion. When people are robbed of everything, still having small things such as names, hairstyles, and language allows for unity. Rituals, customs, and other (what may seem minuscule to outsiders) details can bring people of the same ethnic group together despite all of the violence that has been endured.

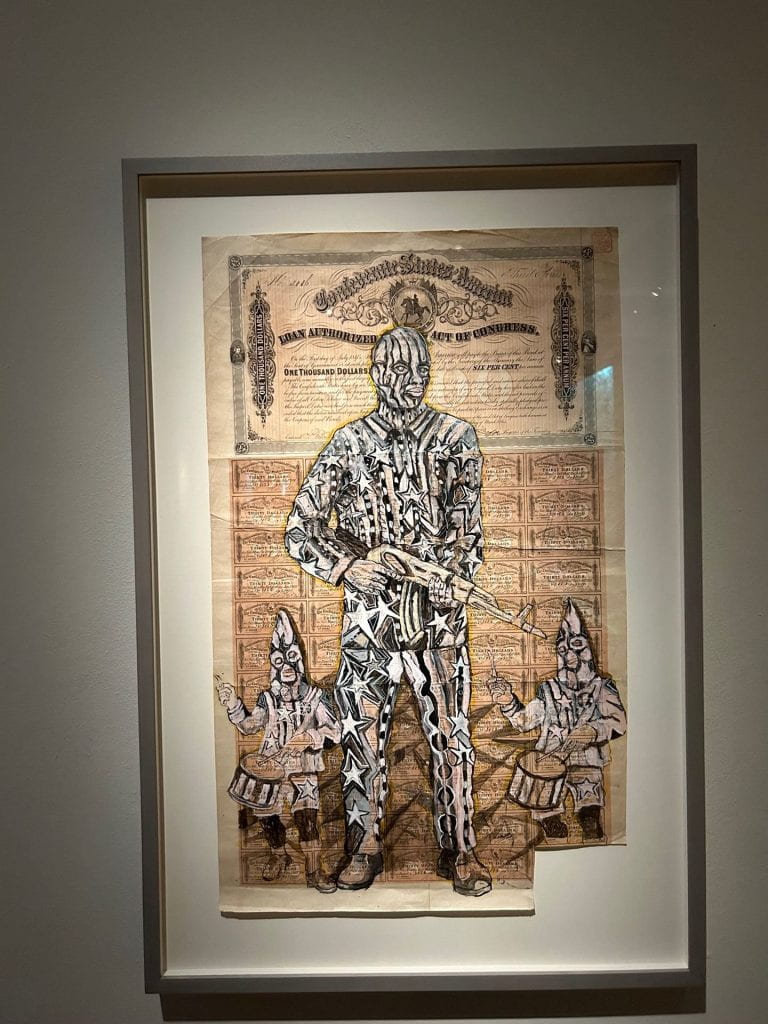

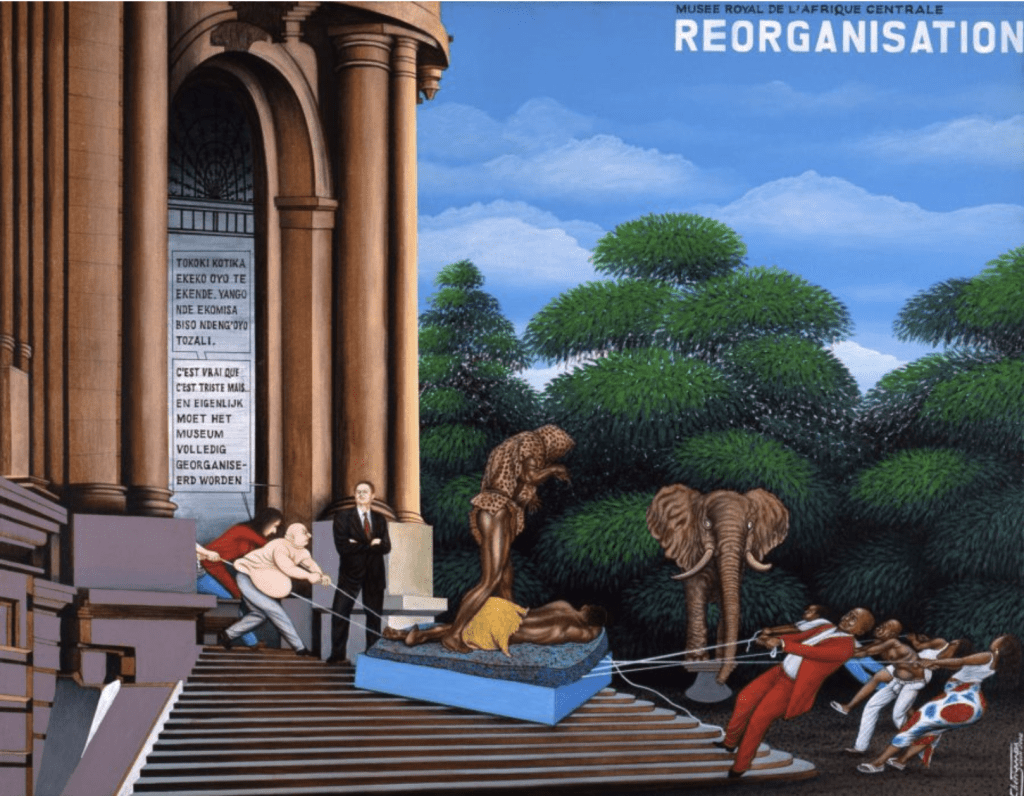

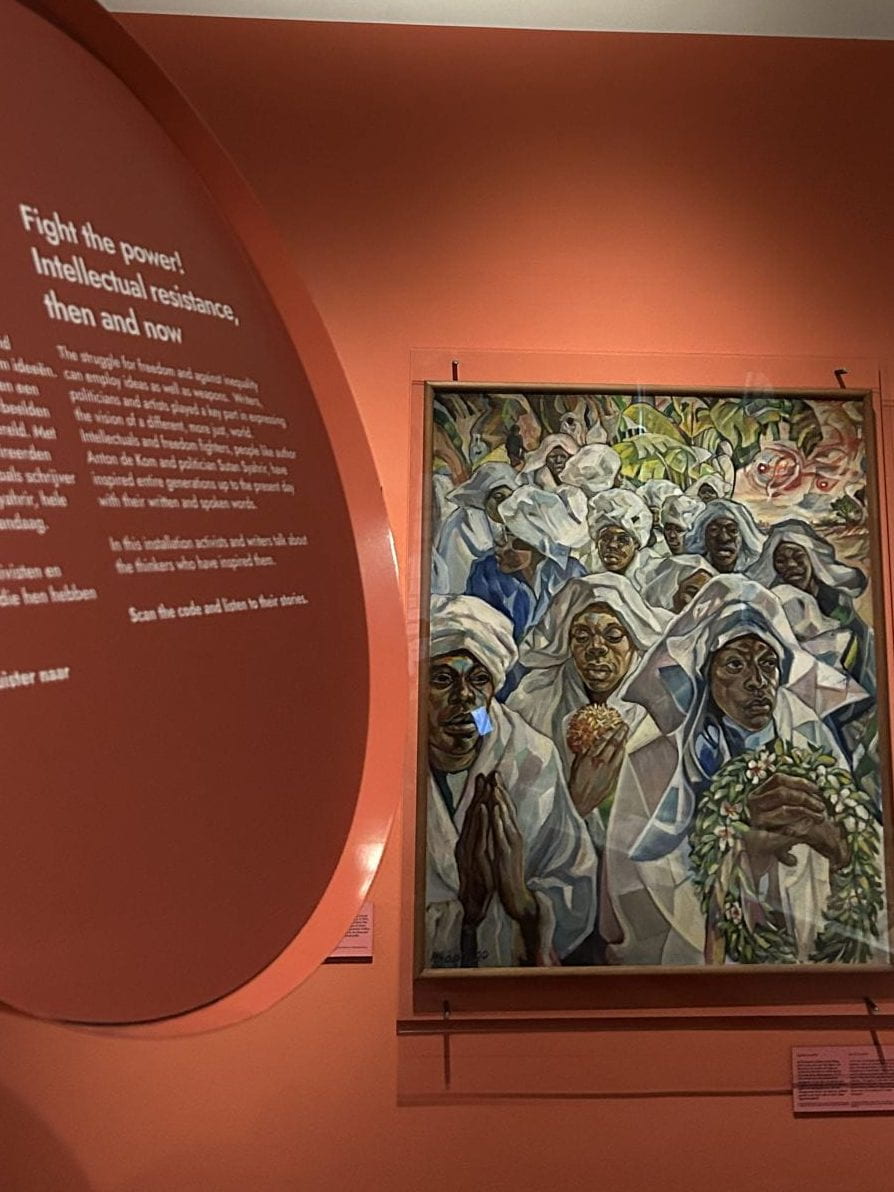

Along with the resilience of colonized groups of people, there is resistance. During the colonization of Africa, there were different forms of resistance taking place. This included military resistance, everyday resistance (in the form of sabotage and absenteeism from work), and ideological resistance. One of the more powerful forms, in my opinion, to defy oppressors is ideological and intellectual resistance through literature and art. Pan-Africanism, the celebration of African achievement, is a popular form of ideological resistance.

“Emancipate yourself from mental slavery”

~ Bob Marley

Pan-Africanism dates back to the 19th century originating as “Ethiopianism” due to the frustration of European discrimination and racist ideology. Later in the 20th century the main leaders of the Pan-Africanism movement were Marcus Garvey and W.E.B DuBois. Garvey realized that the majority of the Black population had similar experiences when it came to discrimination. With influences of earlier Pan-Africanist leaders, founded the Universal Negro Improvement Society (UNIA) in 1914 in Jamacia and later founded the newspaper Negro World in 1918 in the U.S. He gained followers mainly because of his avocation to return to Africa, the establishment of buying from black-owned businesses (something we still see and do today), and promoting of African pride(Laumann 2013).

“The Black skin is not a badge of shame, but rather a glorious symbol of national greatness.”

~ Marcus Garvey

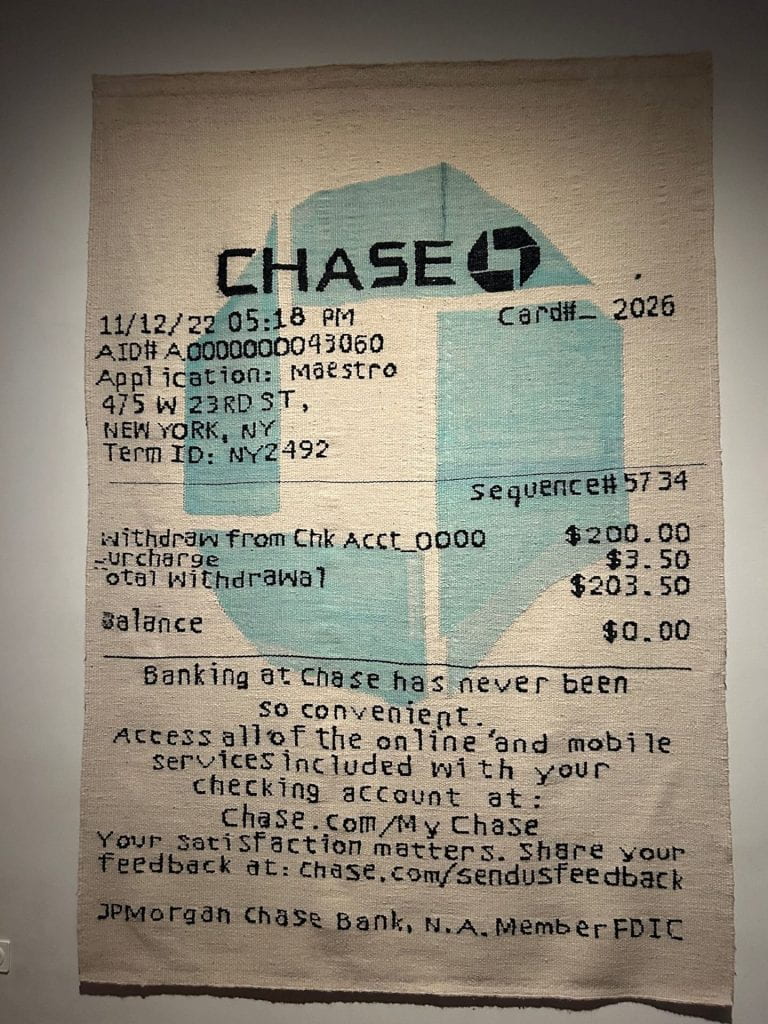

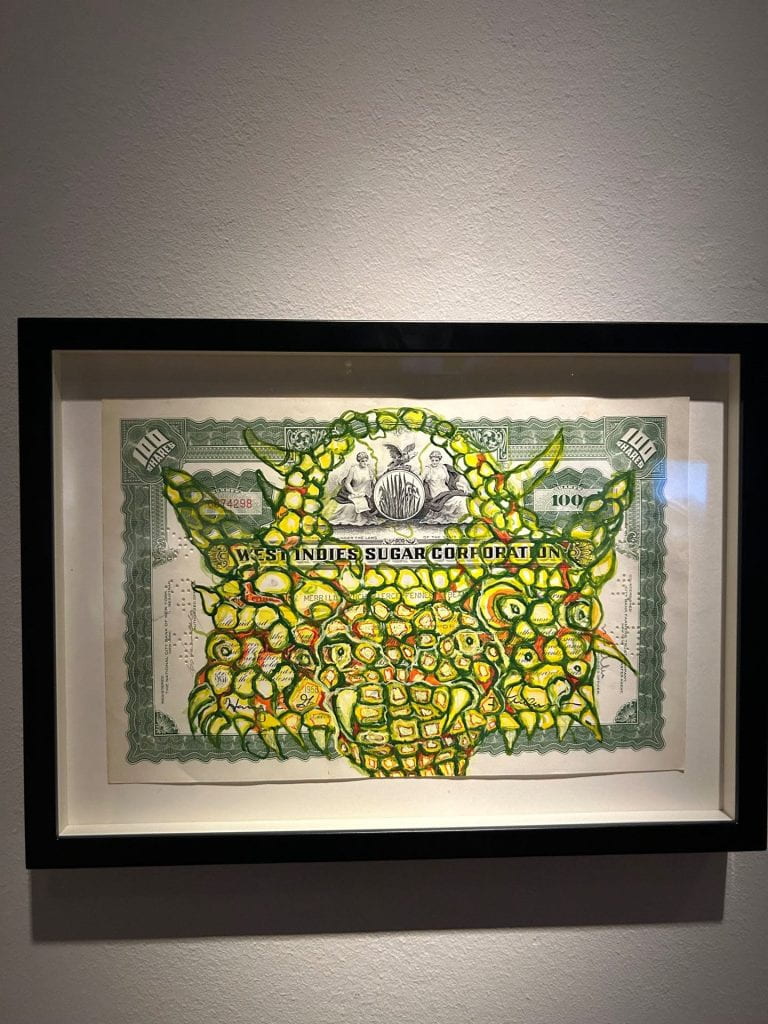

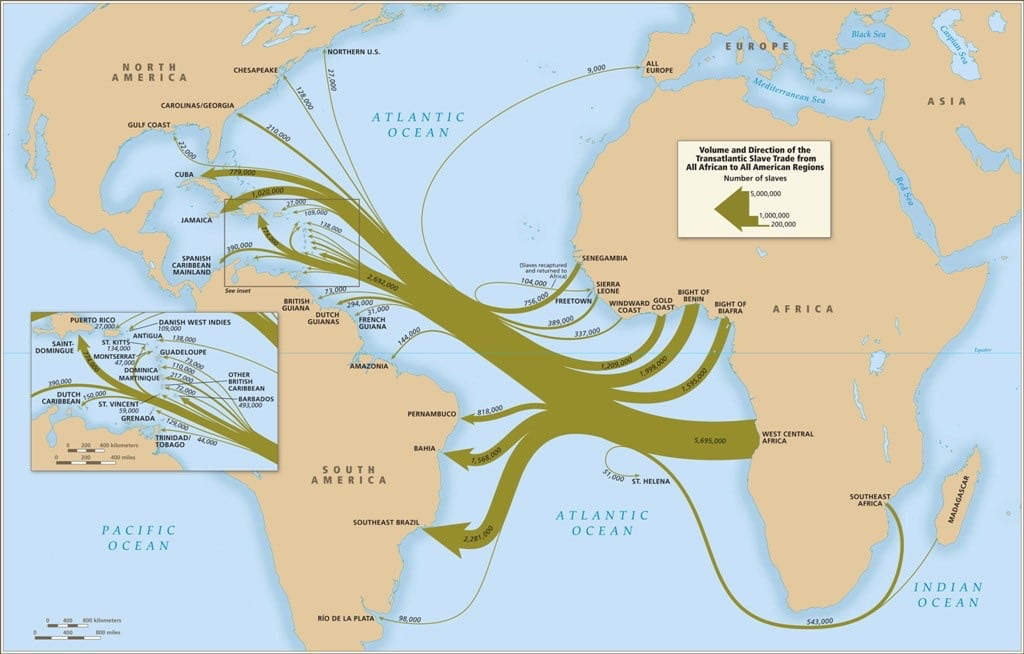

DuBois, founder of the National Association for the Advance of Colored People (NAACP), was an activist and author with one of his most famous books being The Souls of Black Folks. DuBois felt that colonialism and oppression were direct results of capitalism (Laumann 2013) and from my time abroad and time spent learning about colonial Africa, I don’t disagree. Africans were exploited and dispersed for the demands of European commodities that have now become global demands, from the sugar plantations that were in the Caribbean to Cobalt mines in the Congo. The goal of Pan-Africanism is to unite all and to celebrate Africa and the diaspora, and unity is a result of resilience and resistance.

I am beyond grateful for my time spent in Belgium and the Netherlands soaking up information, new places, and different cultures. Knowledge is power and with that, I have taken away that if imperialist societies took the time to thoroughly educate their citizens, the narrative of both the colonizer and colonies would drastically change.

Resources:

Adamek, Tayo. 2018. The African Diaspora. Map. BYTE Youth https://www.yukonyouth.com/the-african-diaspora-what-is-it/

Laumann, Denise. Colonial Africa. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013